In Part 1 of our 7-part series on Britain and the origins of the Industrial Revolution, we introduced it as a time of gradual but fundamental change (transformation) in Britain from a dependency on organic resources and means of production to mechanized production using sources such as coal. Along the way, Britain became more urbanized and expanded its markets domestically and internationally, becoming the world’s foremost power by the early to middle of the 19th century. How did this happen? What preconditions facilitated this transformation?

Part 2 examines one of these preconditions: Improved Farming and Population Growth.

Improved farming and population growth provided essential preconditions for industrialization. Factory owners would need more people to grow their labour force and to buy their products. More people required more food, and this growing demand hastened agricultural innovations that, in turn, facilitated population growth. During the 17th century, farms gradually depended less on environmental whims and offered more predictable and productive yields. Before these changes, people lived according to a traditional cycle of population and productivity. When food production reached a limit based on available land and agricultural methods, the population reached a threshold, declined, and grew again until it reached production limits. This pattern stemmed from a system where agriculture involved subsistence for peasants and income for landlords and common lands were used for grazing livestock and fuel (e.g. wood).

Commercial Farming, Cash Crops and Enclosures

Various agricultural innovations drastically improved farm production and broke this cycle. One fundamental change was the development of market-oriented agriculture. Landowners, mainly nobles, increasingly fenced off common lands to create land enclosures focused on growing cash crops for sale and export rather than local consumption. Governments, who sought noble support and tax revenues, supported these measures against peasant resistance – sometimes with armed forces. This displaced peasants and many became wage earners on far or factories.

These cash crops created a greater demand for larger fields. Historian John Merriman writes, “Between 1750 and 1850 in Britain, 6 million acres – or one-fourth of the country’s cultivatable land – were incorporated into larger farms. (518) The trend toward commercial agriculture was well on its way.

Farming Innovations: Crop Rotation and Animal Husbandry

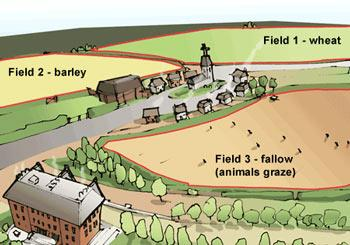

As farming became more commercialized, farmers became more specialized and adopted practices such as crop rotation. Crop rotation differed from conventional agriculture, which saw farmers plant the same crop in the same place every year while leaving some fields fallow for two or three years to replenish their nutrients. Problems arose as these crops drew the same nutrients out of the soil, thus depleting it. Moreover, pests and diseases could establish themselves more readily. Crop rotation addressed these problems. Planting different crops sequentially on the same land optimizes soil nutrients and helps prevent pests and weed infestations. For instance, a farmer might plant corn one season and beans the next.

Healthy soil and healthy crops drastically improved food production. Innovators like Robert Bakewell (1725-1795) improved animal husbandry, enhancing food supplies – particularly protein.

Technological Advances

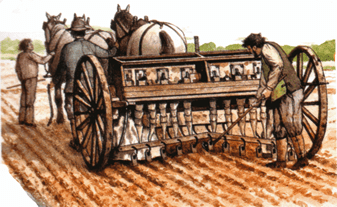

Technological advances also increased productivity. Farmer Jethro Tull (1674-1741) created the seed drill that planted seeds in deep soil, a drastic improvement over simply casting seeds on or near the surface where they would be more vulnerable to the elements or animals. Iron plows allowed farmers to turn the soil more deeply.

Charles “Turnip” Townsend (1674-1738) learned how to cultivate sandy soil with fertilizer from the Dutch and expanded arable lands (Kagan 495).

More production and more food options.

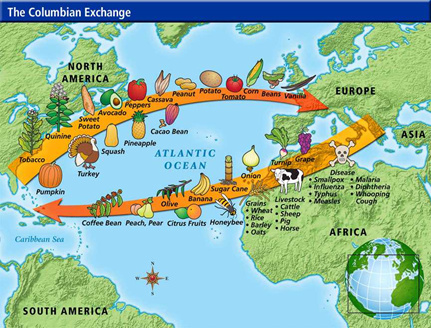

Throughout the next century, these farming innovations meant fewer people could produce more food, and more food could be grown per acre. Improved food production also created more varied and calorie-rich diets –fundamental contributors to population growth. The potato and maize – two nutritious foods from the Americas played essential roles. Imported from the Americas, the potato became especially widespread throughout Europe. Donald Kagan writes, “On a single acre, a peasant family could grow enough potatoes for an entire year. (Kagan, 497). These local developments were bolstered by what Alfred Crosby called the “Columbian Exchange” – the exchange of food, animals, and disease between Europe and the Americas—from this, Europe gained maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and cod. Indentured servants and slaves – laboured to produce these essential foodstuffs.

Overall, production rates soared. Merriman points out, “England produced almost three times more grain in the 1830s than the previous century.” (Merriman 518) Besides feeding more people, farms produced more fodder for livestock and helped create a more reliable milk and meat source. More livestock also meant more fertilizer (manure). Fish like the cod harvested off Canada’s east coast offered another protein source.

Nutrition, Sanitation and Disease

Better nutrition went hand in hand with improved disease prevention and treatment. Diseases like tuberculosis, influenza and dysentery still took many lives but conditions generally improved as cities gradually improved water supplies and waste management. Medical practices only played a minor role until well into the 19th century. However, Edward Jenner’s vaccines for smallpox in the 1790s helped contain lethal outbreaks, and vaccinations would help stave off other diseases in the next century.

Rapid Population Growth

Over the eighteenth century the turn of the century, the population of England and Wales increased from about 5.5. million to approximately 10 million and 20.9 million by 1850. (Cipolla, 29) Growing numbers in urban centers like Manchester provided cheaper labour for factories to flourish. Moreover, the combined factors of population growth and increased income per head led to more purchasing power and growing demand for products – – two essential factors for industrial growth.

Stay tuned for our next blog in our 7-part series on the origins of the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

Part 3: Access to Foreign Markets and Capital Investment

You must be logged in to post a comment.