“one of the scariest monsters on earth.” Dr. Michael Osterholm.

Smallpox, known by various names like “the speckled monster”, “the red plague”, “Hunpox”, and the “great pox”, was an undiscriminating killer of all races and classes. It might have killed Marcus Aurelius and almost finished Elizabeth I. The Habsburg Emperor Joseph I died from the disease in 1711. Smallpox shaped migrations, influenced military outcomes and undermined governments. Over millennia, the disease spread worldwide and stood as one of the most formidable enemies of human existence, killing billions.

The quest to understand and combat smallpox had spanned centuries. In 1796, English physician Edward Jenner (1749-1823) achieved a historic breakthrough by creating the first vaccine. It was a milestone in the history of medicine but the disease lingered. Its continued impact into the 20th century is a stark reminder of the importance of eradicating such diseases. 1969, the World Health Organization (WHO) finally declared that smallpox was eradicated.

What is Smallpox?

To fully appreciate the magnitude of this achievement, it is crucial to comprehend the nature of smallpox. We must understand its characteristics, its mode of transmission, and its impact on diverse populations worldwide. Diseases happen when pathogens (the agents that cause disease) such as viruses, bacteria and fungi infect the tissue of a living being. Pathogens include viruses, bacteria, and fungi. They infect the tissue of living beings. Symptoms occur when the pathogen releases toxins as they multiply, spread or even kill cells. Diseases occur when pathogens infect the tissue of a living being.

Smallpox is a virus that is a parasite of animals, plants, and bacteria. Some examples include the common cold, influenza, smallpox, AIDS, herpes, hepatitis, polio, and rabies. As parasites, viruses need a host to reproduce. They achieve this by infecting host cells and hijacking their machinery to survive and multiply. Outside of a host, viruses are inert. Contagious diseases can be passed between organisms (e.g. person to person) in various ways – direct contact (touch), indirect contact (with an infected object), and airborne (coughing, sneezing). When infection sets in, it sickens or even kills us.

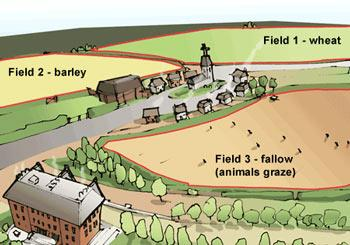

Like measles and whooping cough, smallpox is a so-called “crowd disease.” This term is used to describe diseases that spread rapidly in densely populated areas. They are particularly dangerous and difficult to control. This is due to their high transmission rates and potential for widespread outbreaks.

Microscopic image of a virus

Smallpox is a Zoonotic disease. It is shared among people and sometimes between other animals like bats, monkeys, and livestock. Smallpox infects humans but not other animals. Other zoonotic diseases include measles, HIV, AIDs, chicken pox, and SARS. Collectively, they are the deadliest diseases in human history.

Arguably the most lethal of the lot, smallpox is an influenza (flu)that scientists later discovered is caused by an Orthopoxvirus. (Snowden,87) The medical name for smallpox is variola virus. Virologists identify two kinds of smallpox. Variola major has a mortality rate of 25 to 30 percent. Variola minor has mild symptoms and a death rate of 1 percent or less. Variola major is the focus of this study.

What made smallpox so deadly?

Smallpox (variola major) has many dangerous traits, including its mode of infection and its adaptability to various climates. Regarding infection, it is highly contagious and transmitted mainly through droplets exhaled through coughing or sneezing. It can only be spread from human to human, not to other animals. The disease can also spread from the corpses of smallpox victims and contaminated items like linens.

Abetting its spread is that smallpox infects a host slowly with no immediate signs of illness. From the time of infection, the incubation period is nine to fourteen days. The infected experience symptoms such as fever, chills, headaches, and nausea. These symptoms could be confused with other ailments. Since symptoms do not appear for a week or two, people could unknowingly infect others for a week or two. After incubation, the overt symptoms include lesioning and skin rashes. Survivors could be blinded or permanently scarred. Some died. It ultimately kills by attacking the internal organs – the liver, lungs and heart. Infants are the most vulnerable. Survivors of smallpox did not become infected again, an essential trait that facilitated its eventual eradication.

Smallpox also demonstrated a remarkable ability to survive in diverse climates. This includes the cooler temperatures of Northern Europe. This adaptability allowed smallpox to extend its reach far beyond the tropical regions where diseases like malaria thrived. Adaptability, contagiousness, and lethality made smallpox a pervasive and influential force in shaping human events. Its resilience, even in the face of diverse climates, underscores the gravity of this deadly disease’s impact on human history.

Smallpox and History

Scholars increasingly acknowledge the role of smallpox and other diseases in the unfolding of history. In his 2019 book, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Frank Snowden writes that diseases are “a major part of the ‘big picture’ of historical change.” They are crucial for understanding historical development. They include societal developments such as economic crises, wars, revolutions, and demographic change. (2) Human history is littered with diseases like the plague, cholera, and the Spanish flu. Smallpox (variola major) is one of history’s most formative diseases and perhaps the deadliest.

Origins

Where did smallpox come from? Archaeological findings suggest smallpox and other diseases have a very long history. These diseases grew out of what sociologist Jonathan Kennedy calls “an epidemiological revolution.” This revolution followed hot on the heels of the Neolithic Revolution (c 10,000 to 8,000 BCE). This period saw some humans change from nomadic lifestyles to sedentary farm-based communities with more sustained interaction with domesticated animals. (Kennedy, 43). So, while we do not know the exact origins of smallpox, scholars have extrapolated its likely origins. Since it is a Zoonotic disease, closely related to cowpox found in animals like bovines and rodents, it likely grew out of the Neolithic period.

Early Cases.

Even with today’s sophisticated archeological methods, it is difficult to determine the first cases of smallpox. The scant written records and rudimentary scientific knowledge of ancient peoples’ diseases mean that potential cases of smallpox could also be other diseases, such as measles, the bubonic plague or typhus. Archeologists might have found evidence of instances of smallpox in ancient Egypt. Three mummies, including the young Pharoah Ramses V, who died in 1157 BC, were found with what looked like pockmarks. Written sources from Asia describe potential cases of smallpox in China (1122 BC) and India (1500 BC). Again, these are not definitive.

Smallpox and the Mediterranean

Whatever its specific origins, smallpox eventually spread throughout the world, enabled by denser populations and improvements in transportation technology that facilitated more human interactions through trade, migration and war. Egypt, a potential source of smallpox, sits south of the Mediterranean Sea, a hub of interaction. As historian David Abulafia points out, “The sea routes of the Mediterranean have always provided a means for the transmission of pandemics,” like the Justinian plague in the sixth century AD and the Black Death in the fourteenth century AD. (144)

Some scholars believe smallpox impacted the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), which saw Athens fight Sparta for regional supremacy. In 430 BC, the Plague of Athens devastated that city, killing a quarter of the population over three years and severely weakening the Athenian war effort, thus facilitating Sparta’s victory. (Kennedy, 60). Other scholars have suggested measles or the bubonic plague. It is difficult to discern since contemporaries, as Abulafia points out, “saw these events as divine punishment rather than pathologies.” (144) Thucydides is often cited for his observations of the Athenian plague but does not describe the disease symptoms in a manner that would verify it was smallpox.

For some, smallpox is the prime suspect behind the Antonine Plague (164-165 AD) in the Roman Empire during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE). Fatality estimates vary but may have been in the millions. Historian Mark Thompson and others suggest that soldiers brought the disease back home after fighting in Mesopotamia. Contemporary Greek physician Galen described the symptoms as “diarrhea, high fever, and the appearance of pustules on the skin after nine days.” (Kerhaw 211). By this time, the Roman Empire displayed vulnerabilities and epidemics such as the Antigone Plague, further weakening its resilience by disrupting the Roman economy, labour force, and army.

More Reliable Accounts

We find more reliable accounts of smallpox and other diseases as written records improve. However, only in the fourth century AD “can we find the first unmistakable description of smallpox in China. (Hopkins, 104). There is some debate about how it initially entered China. Some argued that it first came from the Huns, a nomadic tribe to the north. Hopkins, for instance, points to early accounts of what might be smallpox in China from around 250 BC and introduced by the Huns a few decades before the creation of the Great Wall. Some Chinese called it the “Hunpox” epidemic, reflecting their sense of its source. (Hopkins, 101) Again, the records are scant, so confirming that this “Hunpox” was smallpox is difficult. Other scholars challenge the “Hun origin” theory and suggest smallpox might have been introduced to China centuries later via India, along with the introduction of Buddhism around 65 AD. (Hopkins, 104).

Smallpox might have spread to the Korean peninsula around 48 AD. While Japan was separated from the mainland by water, the disease eventually reached the island country around 585 AD and wreaked havoc. Historian Charles Holcombe estimates that an epidemic in 735-737 AD may have killed a quarter of Japan’s population. (Holcombe, 118)

Smallpox became established as an “Old World Disease.”

Smallpox eventually migrated throughout Europe, a continent significantly less densely populated and travelled than Asia, the Near East, and the Mediterranean until the early modern era. Historian Frank Snowden and other scholars suggest that the virus spread during the Crusades of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, as soldiers and pilgrims travelled back and forth between Europe and the Levant, the general area of what is now Israel, Lebanon, and Syria (97, Snowden). Over time, as European populations increased and interregional interactions became more frequent, smallpox and other diseases became endemic.

Smallpox became endemic throughout most parts of Eurasia, or the “Old World.” Biologist Frank Fenner writes, “By 1000 AD, smallpox was probably endemic in the more densely populated Eurasian landmass from Japan to Spain and the African countries on the southern rim of the Mediterranean. (402). By the 14th century, smallpox was established in Germany, Spain and France. By the latter half of the 16th century, smallpox was endemic to Europe.

Smallpox, the “New World” and the Columbian Exchange

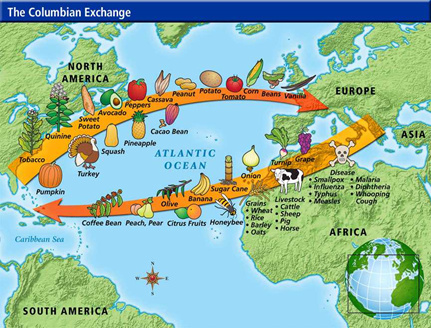

Smallpox finally made its way to the Americas in the sixteenth century. Advances in navigation and shipbuilding and a growing appetite for trade with the faraway lands of India and China compelled European powers to seek reliable sea routes to these markets. Christopher Columbus reached the Americas in 1492. Later voyages and settlements led to what Alfred Crosby called the “Columbian Exchange,” the transatlantic transmission of technologies, foods, and diseases.

As part of this exchange, smallpox served as the primary biological culprit (other Old World diseases like measles contributed) in an epidemiological onslaught that would lead to the death of more than 90% of the indigenous population of the Americas (60.5 million in 1500 to 6 million a century later).

This demise facilitated the eventual European domination of the “New World. (Kennedy, 127). Moreover, the decimation of the Indigenous population, coupled with malaria’s devastation of European settlers in the warmer parts of America, encouraged, from the late 17th century onwards, the import of African slaves who had developed more immunity and so provided a more secure labour force. African slaves, travelling in tightly packed ships that served as incubators, also unwittingly spread smallpox and other diseases to the Americas.

Smallpox After 1600 AD

As the world became more interconnected through war, migration and trade, smallpox became endemic to many parts of the world and continued to impact human affairs. Snowden writes that in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, smallpox “replaced bubonic plague as the most feared of all killers.” (97). Most people became infected during their lifetimes. While indigenous people of the Americas suffered the worst devastations, Europeans still felt its deadly touch despite variolation and other mitigating factors, like improved public hygiene and better nutrition. People were more likely to die from infectious diseases than today’s leading causes of death, cardiovascular disease and cancer. (Berman, 13) Some estimates suggest smallpox caused a tenth of all European deaths during the 18th century and “a third of all deaths among children younger than ten.” (Snowden 98). It was also the continent’s leading cause of blindness.

In Asia, smallpox shaped territorial competition and reduced local population numbers. In 1759, China’s Qing dynasty defeated the Western Mongols. Military prowess partially explains the outcome, but as historian Charles Holcombe writes, the Mongol’s demise might have been more from smallpox, “a disease to which Mongols were shockingly vulnerable.” (168, Holcombe).

As mentioned earlier, smallpox had wiped out a quarter of Japan’s population in 735-7 AD. Japan experienced many epidemics in the following centuries, particularly in its more densely populated regions. However, as populations spread to frontiers, so did smallpox. During the 19th century, the disease spread to Northern Japan, with Japanese settlers migrating to Hokkaido, drastically reducing the minority Ainu population.

Smallpox also thrived in India. Jayant Banthia and Tim Dyson note that “case fatality in India from smallpox was high – in the vicinity of 25-30 percent in unprotected populations, higher than recent estimates for eighteenth-century Europe.” (676)

Edward Jenner and the First Vaccine (1796)

Edward Jenner created a smallpox vaccine (the first ever vaccine) in 1796, but it would take time to distribute globally. In the meantime, smallpox continued to thrive. The Franco-Prussian War triggered a smallpox pandemic of 1870–1875 that claimed 500,000 lives. Vaccination was mandatory in the Prussian army, but many French soldiers were not vaccinated, so smallpox outbreaks among French prisoners of war spread to the German civilian population and other parts of Europe.

This public health disaster ultimately inspired stricter legislation in Germany and England, though not in France. Smallpox continued to wreak havoc into the next century and “may have caused the death of as many as 300 million people in the 20th century alone. (Khan and Darwez,21)

Conclusion.

Dr. Michael Osterholm’s description of smallpox as “one of the scariest monsters on earth” is not hyperbole. The disease killed billions and caused immeasurable suffering. Due to its adaptability and resilience, smallpox thrived on most continents. Its demographic devastation, most notably in the Americas, profoundly impacted human history.

It’s one weakness is that it can’t infect a person more than once, facilitating the effectiveness of vaccine treatment and the disease’s demise. The history of smallpox and other diseases offers valuable lessons and insights. We would be wise to heed them in a world with a growing population and greater interaction.

Bibliography

Alden, Dauril, and Joseph C. Miller. “Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil, 1560-1831.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 2 (1987): 195–224. https://doi.org/10.2307/204281.

Banthia, Jayant, and Tim Dyson. “Smallpox in Nineteenth-Century India.” Population and Development Review 25, no. 4 (1999): 649–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/172481.

Berman, Jonathan M. Anti-Vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed Movement. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press, 2020.

Chang, Chia-Feng. “Disease and Its Impact on Politics, Diplomacy, and the Military: The Case of Smallpox and the Manchus (1613–1795).” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 57, no. 2 (2002): 177–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24623679.

Fenner, Frank. “Smallpox: Emergence, Global Spread, and Eradication.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 15, no. 3 (1993): 397–420. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23331731.

Fenner, Frank. “SMALLPOX IN SOUTHEAST ASIA.” Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 3, no. 2/3 (1987): 34–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40860242.

Holcombe, Charles. A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Hopkin, Donald R. The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002.

AMALIE M. KASS. “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic:” Massachusetts Historical Review (MHR) 14 (2012): 1–51. https://doi.org/10.5224/masshistrevi.14.1.0001.

Kennedy, Jonathan. Pathogens: A History of the World in Eight Plagues. Toronto: Random House, 2023.

Kershaw, Stephen P. A Brief History of the Roman Empire: Rise and Fall.

Khan, Gazala, and Sazzad Parwez. “A Historical Narrative on Pandemic Patterns of Behavior and Belief.” Journal of Global Faultlines 9, no. 1 (2022): 21–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48676220.

Li, Yu, Darin S. Carroll, Shea N. Gardner, Matthew C. Walsh, Elizabeth A. Vitalis, and Inger K. Damon. “On the Origin of Smallpox: Correlating Variola Phylogenics with Historical Smallpox Records.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, no. 40 (2007): 15787–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25449217.

Manley, Jennifer. “Measles and Ancient Plagues: A Note on New Scientific Evidence.” The Classical World 107, no. 3 (2014): 393–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24699810.

Martin, Sean. A Short History of Disease: Plagues, Poxes and Civilizations. Herts, UK: Pocket Essentials, 2015.

Mnookin, Seth. The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear. New York: Simon and Shuster, 2011.

Morens, David M., and Robert J. Littman. “Epidemiology of the Plague of Athens.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 122 (1992): 271–304. https://doi.org/10.2307/284374.

Pas, Remco van de. “Epidemics in the Colonial Era.” Globalization Paradox and the Coronavirus Pandemic. Clingendael Institute, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24671.6.

Osterholm, Michael T. and Mark Olshaker. Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2020.

Riley, James C. “Smallpox and American Indians Revisited.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 65, no. 4 (2010): 445–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24631803.

Snowden, Frank M. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Yale University Press, 2018

Sohal, Sukhdev Singh. “Revisiting Smallpox Epidemic in Punjab (c. 1850 – c. 1901).” Social Scientist 43, no. 1/2 (2015): 61–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24372964.

Thein, MM, LG GOH, and KH Phua. “The Smallpox Story: From Variolation to Victory.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 2, no. 3 (1988): 203–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26720502.

Thomson, Mark. “Junior Division Winner: The Migration of Smallpox and Its Indelible Footprint on Latin American History.” The History Teacher 32, no. 1 (1998): 117–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/494425.

Vögele, Jörg, Luisa Rittershaus, and Katharina Schuler. “Epidemics and Pandemics – the Historical Perspective. Introduction.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. Supplement, no. 33 (2021): 7–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27087273.

Warren, Christopher. “Could First Fleet Smallpox Infect Aborigines? – A Note.” Aboriginal History 31 (2007): 152–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24046734.

You must be logged in to post a comment.