Concepts have histories. They appear at specific times, change meanings at times, and disappear sometimes. Adam Przewarski

For a political system that affects the lives of so many, authoritarianism remains a surprisingly fuzzy concept. Ruth Ben-Ghiat

In the introduction to our series on authoritarian tactics, we noted how a significant increase in global authoritarianism since 1990 has spurned the publication of numerous books, articles, and podcasts that focus on authoritarianism past and present. Many of these contributions warn of authoritarian’s danger to liberal democracies and remind us of the dangers of past autocratic leaders like Mussolini, Stalin and Hitler.

But what is authoritarianism? How does it differ from democracy, totalitarianism, and other forms of government? Are there different versions of authoritarianism? If so, what discernible traits do they share? This series of blogs focuses on “authoritarian tactics,” but it is worthwhile to begin by exploring how people have defined authoritarianism. This blog will explore how scholars have contrasted authoritarianism with democracy and totalitarianism. We also investigate how modern scholars have traced how post-19th-century authoritarianism evolved from the early communist and fascist regimes to various military coups and finally to the 1990s and beyond with what scholars call the “new authoritarianism.”

Authoritarianism: A Relatively New Term.

As political scientist Adam Przewarski writes, “Concepts have histories.” (17). Political terms such as democracy, monarchy, dynasty, and communism have existed for centuries. “Authoritarianism” is relatively new, initially conceived as a regime distinct from “totalitarianism,” another term created in the 20th century to describe the regimes of Stalin’s Soviet Union, Hitler’s Germany and, for some, Mussolini’s Italy. (Przewarski,18) These totalitarian states eventually faltered. However, commentators continued to use authoritarianism to describe various regimes in the latter half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, ranging from Franco’s Spain to Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya and Augusto Pinochet Ugart’s Chile, who achieved power through military coups to democratically elected Viktor Orban in Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Do these regimes have enough similarities to be collectively defined as “authoritarianism”? One consistent claim among scholars is that authoritarianism is anti-democratic. We will begin here.

Authoritarianism as “Anti-Democratic”

Commentators frequently contrast authoritarianism with democracy, another problematic term. The notion of a government by the people misleads in the sense that not all people actively participate in politics. Few do. Representative democracy, whereby people elect officials to rule on their behalf, is closer to reality in countries claiming to be democratic but remains lofty as many peoples’ interests are readily neglected. In various cases, government “by the people” has been delimited by discriminations of race, gender and class. Athenian democracy, for instance, involved public debate and consent but excluded, among others, women and slaves. Most Western democracies, such as Canada and the United States, did not extend voting rights to women until after World War One. These days, the financial backing of electoral candidates and gerrymandering undermine equal public involvement and influence. Philosopher Peter Cave notes that contemporary democracies “are usually oriented to professional politicians competing for votes to become the people’s representative.” (59). He adds that financial support and charisma play big roles in the “public’s careful scrutiny of policy platforms.” ( 59)

Still, scholars use democracy or principles of democracy as counterpoints to authoritarianism. Noting how definitions of democracy have changed since antiquity, Przeworski writes that “these days” democracy means “a system where power is exerted in the name of and on behalf of the people by the process of elections that also allow them to vote out an incumbent (e.g. an elected President or Prime Minister). In other words, democracy is essentially “rule by consent” as legitimized by free and fair elections.

This notion of “public consent” is central to definitions of authoritarianism. For instance, the Dictionary of Political Thought describes authoritarianism as “The advocacy of government based on an established system of authority rather than on explicit or tacit consent.” (Scruton 32). The Chamber’s Dictionary of World History offers a more substantial definition, defining authoritarianism as

A form of government advocating such government is the opposite of democracy in that the consent of society to rulers and their decisions is not necessary. Voting and discussion are not usually employed except to give the government the appearance of democratic legitimacy, and such arrangements remain firmly under the control of the rulers. Authoritarian rulers draw their authority from what are claimed to be special qualities of a religious, nationalistic, or ideological nature, which are used to justify their dispensing with constitutional restrictions. Their rule, however, relies heavily upon coercion. (64)

This Chamber’s definition also focuses on consent, noting that authoritarian regimes do not embrace “democratic practices” such as voting and open discussion but sometimes allow them to “give the appearance of legitimacy.” Authoritarian authority also stems from sources other than public consent, such as religion (the Papal theocracies of the Holy Roman Empire, post-1979 Iran), nationalism (Russia’s Putin), and ideology (Lenin or Mao and their brands of communism). These sources of authority transcend constitutional restrictions in the name of the greater good of the people (e.g., the nation) and allow governments to forgo public consent and consolidate political power.

Political scientists, historians and journalists elaborate on these general descriptions of authoritarianism as “anti-democratic.” Besides public consent, they refer to democratic qualities such as pluralism, freedom of expression and limits on executive power. Political scientist Dr. Martha Crone defines authoritarian regimes by the “absence” of democratic characteristics, namely universal suffrage, free and fair elections, free competition of political parties, independent judiciary, freedom of press, speech, assembly, and religion. Journalist and historian Annie Applebaum refers to authoritarianism’s anti-pluralist mindset. She writes, “It is suspicious of people with different ideas. It is allergic to fierce debates. Whether those who have it derive their politics from Marxism or nationalism is irrelevant; it is a frame of mind, not a set of ideas.” (16) This frame of mind, as Applebaum puts it, encourages public conformity to government directives while discouraging dissent.

One of the more notable efforts to define authoritarianism hails from Yale political scientist Juan Jose Linz (1926 -2013). Like Crone and Applebaum, he highlighted a limited political pluralism that constrains political alternatives (e.g. competing political parties) to the incumbent power. Linz also highlighted authoritarian legitimacy based on fear rather than a reason-based platform. Examples here include Chile’s Pinochet’s (1973-1990) fight against leftist forces and Vladimir Putin’s emphasis on the threat of “the West.” These fears often focus on a malicious threat but can also refer to economic problems or loss of social status of particular groups. Linz adds that authoritarian leaders have vague and shifting executive powers. A modern-day example would be Russia’s Putin, who won the election in 1990 but drastically increased his powers while exceeding the traditional two-term limit as we approach 2024.

It should be noted that Linz’s definition of authoritarianism focused on its anti-democratic nature and how it differed from totalitarianism. With that in mind, let us turn our attention to totalitarianism.

Authoritarianism as Distinct from Totalitarianism

All within the state, none outside the state, none against the state. Benito Mussolini.

So far, the definitions of authoritarianism focus on traits deemed anti-democratic. However, totalitarian regimes also have these antidemocratic qualities. So, why identify a regime as authoritarian rather than totalitarian? Is there an essential difference? As Adam Przewarski writes, “We need to ask if there is something specific to authoritarianism that distinguishes it as a type of dictatorship, other than a watered-down totalitarianism that would make either term “redundant.” (19).

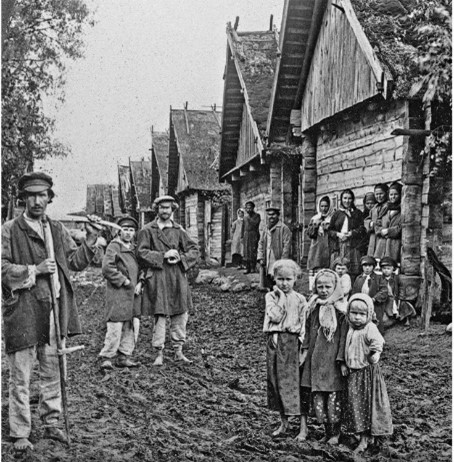

Before focusing on distinguishing features, we should explore what scholars mean by totalitarianism. One place to begin is Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), who focusedon Nazi Germany (1933-1945) and Stalin’s Soviet Union, particularly from the great purges of 1927 and 28 to the Soviet leader’s death in 1953. Arendt identified various characteristics that defined these polities as totalitarian. One was totalitarianism’s anti-pluralism, which relegates everyone as part of a political mass under the control of a centralized power. Here, class and other differences are erased to favour one identity, and citizens are subservient to the state. Moreover, there is no separation of public and private. The state controls all facets of life. As Marvin Perry writes, “The party-state determines what people should believe, what values they should hold. There is no room for individual thinking, private moral judgement or individual concerns – no natural rights, civil liberties that the state must respect.” (767)

Totalitarianism also aligns with an ideology or “absolute” law. For Lenin and subsequent Russian leaders, Marx’s law of history dictated the eventual collapse of capitalism and the creation of classless societies. In Nazi Germany, the ideology was grounded in “nature”; the eugenics-informed racial theories that saw a superior Aryan race winning the historical racial struggle against “inferior races” such as Jews, blacks, and Slavic peoples. For both regimes, these “inevitable” historical forces justified the state’s drastic and brutal efforts to consolidate its power and quash dissent. Accordingly, Nazi Germany claimed the imprisonment and extermination of certain people accorded with the natural order of things. Stalin justified his purges in line with a historical determinism that led to a classless society. In short, ideology informs a grand narrative that justifies state actions.

In totalitarian regimes, these “inevitable” laws are guided by an “infallible” leader like Hitler or Stalin, whose cult of personality puts them beyond public criticism or restraints. They can act with virtual impunity as the state does their will, which includes mass terror to encourage conformity and punish “enemies of the state.” Hitler ordered mass murders and genocide, and Stalin’s purges of 1937 and 1938 saw millions of Soviet people arrested, sent to labour camps or executed. Show trials and public executions sent a strong message to potential dissidents.

Contemporary definitions of totalitarianism generally align with Arendt. For instance, philosopher Alan Ryan describes totalitarianism as

“a set of political phenomena that includes dictatorship; one-part rule; systematic violence against enemies, including but not limited to political dissidents; the use of state terror as an everyday instrument of government; the destruction or politicization of all institutions save those created by the ruling party; and the systematic blurring of the line between the public and the private; all this in the interests of securing the total control of a political elite over every aspect of life.” (912).

But how is this different from authoritarianism?

Authoritarianism and Totalitarianism: Is There a Difference?

Scholars have addressed this question by identifying distinctive totalitarian traits. According to Ryan and others, one difference is the totalitarian intrusion of every aspect of life, including private life. Alan Ryan writes that Fascism, for instance, was overtly totalitarian in demanding total loyalty to one’s country and deeply hostile to the liberal separation of private and public attachment.” (914). Political scientist Jerzy J. Wiater echoes Ryan, saying, “Totalitarian dictatorships – unlike the authoritarian one – try to extend their power to all aspects of life, making them part of politics.” (78) Totalitarian regimes achieved this in my ways, including mass surveillance and controlling education and speech. Stalin’s Soviet Union, for instance, controlled where people lived, what they consumed, who went to university and what they studied.

Scholars also point to totalitarian leaders’ virtually unbridled power that far exceeds that of authoritarian heads of state. Arendt noted that the totalitarian leader is not bound by any rule of law. In Nazi Germany, for instance, it was the will of the Fuher that ruled supreme. Jose Linz echoes this point, writing that totalitarian leaders are “unconstrained by laws and procedures,” whereas “authoritarian leaders work with a political system within formally ill-defined but quite predictable norms.” (Wiater 78) In short, leaders like Hitler and Stalin could act with impunity as there were no checks and balances on their power. So, while authoritarian regimes included limited pluralism (e.g., other political parties and oppositional media), totalitarian regimes did not allow any level of pluralism. Simply put, Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany did not tolerate any political competition or dissent.

Linz and others also noted that authoritarianism does not involve the elaborate ideologies of totalitarian regimes, nor do they usually “cultivate the cult of the leaders with quasi-religious overtones, making them secular versions of the prophets.” (Wiater 78) For instance, Stalin’s successors, like Khrushchev and Brezhnev, were powerful but did not possess the same cult of personality as Stalin. (Wiater, 78)

Lastly, scholars note that totalitarianism is a particular and rare political entity. For Arendt, only Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union fit the criteria. Other scholars include Mao’s China, Mussolini’s Italy and Kim Il Sung’s Korea. So, there remains some debate about what distinguishes totalitarianism from authoritarianism. However, there seems to be a consensus that totalitarianism is unique in the leader’s unbridled power (unrestrained by the rule of law), the cult of personality, its control of public life, and its deterministic ideology (e.g. Nazism or Stalinist communism).

Old and New Authoritarianism.

While scholars note totalitarianism as a rarity, authoritarianism includes a broader base of regimes based on how they gain and consolidate power. Some identify two general categories: old authoritarianism and new authoritarianism. What is the difference between old and new? One focal point of contrast is how regimes gain and then maintain power. University of Michigan political scientist Erica Franz outlines the two authoritarian types in Authoritarianism: What Everybody Needs to Know (2018).

A regime is authoritarian if the executive achieves power through undemocratic means, this is any means besides direct, relatively free and fair elections (e.g. Cuba under Castro and his brother) or if the executive achieved power via a free and fair election but later changed the rules such that subsequent electoral competition (whether legislative or executive) was limited. (e.g. Turkey under Recep Erdogan). (92)

In short, old authoritarian regimes achieve power without democratic consent, usually via a military coup, and the new ones gain power through fair elections but compromise future elections to prolong power and erode checks and balances on executive power. Let us take a closer look at both options.

Old Authoritarianism

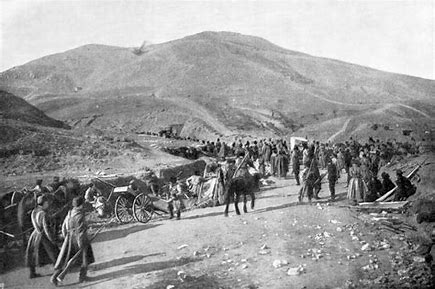

For old authoritarianism, “undemocratic mean” usually involves coups and revolutions from the likes of Lenin in Russia, Franco in Spain, Mao Zedong in China and Pinochet in Chile. None of these regimes were able to control private lives like the totalitarian regimes of Stalin or Hitler, and ideology did not necessarily guide their rule. However, these old authoritarian regimes used explicit coercion and violence to gain and consolidate power. According to political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, these coups happen in two fundamental ways. One way is when someone within the political and military establishment takes over the existing government institutions – a “top-down” movement. Franco and Pinochet, for instance, were military leaders who deposed and replaced the incumbent leadership with military force. In both cases, prominent military leaders took over the existing political and military institutions. The other is a social revolutionary coup. Parties lead this “bottom-up” movement from outside the political or military establishment. Mao Zedong and Fidel Castro gained power through guerilla warfare as leaders outside the political establishment.

New Authoritarianism

The “new” form of authoritarian regimes tends to refrain from violence as a tool of power. Instead, it achieves power through free and fair elections, consolidating power by weakening checks on its power. Scholars describe this process as “democratic backsliding,” which Erica Franz describes as the “changes in the formal political institutions and informal political practice that significantly reduce the capacity of citizens to make enforceable claims upon the government. It is essentially the erosion of democracy.” (Franz, 92) In short, these governments undermine, control, or abolish those institutions, groups or individuals who threaten to abbreviate their political tenure or power. Unlike totalitarian and some old authoritarian regimes, there are competing political parties, but new authoritarians strive to ensure they are not real threats to their power. A telling example is Vladimir Putin of Russia, who won his 1990 election but changed “the rules of the game” to ensure that elections would result in his win. Other contemporary leaders like Victor Orban in Hungary and Turkey’s Precep Erdogan have implemented changes to favour their victories – albeit more subtly than Putin.

Political scientists Steven Lewitsky and Lucan Way describe this as “competitive authoritarianism,” they define as “civilian regimes in which formal democratic institutions exist and are widely viewed as the primary means of gaining power but in which the incumbent’s abuse of the places them at a significant advantage vis a vis their opponent…competition is real but unfair.” (26, Przeworski) This definition would exclude Franco’s Spain and contemporary China, which do not utilize democratic institutions to justify their rule, but would include contemporary leaders such as Putin, Orban and Erdogan, who have won a series of elections.

Besides electoral manipulation, these new authoritarians take other measures by eroding institutional checks on executive power, such as the judiciary, the media and the Constitution. Victor Orban’s Fidesz party won a majority election in Hungary in 2010. A year later, his party made a constitutional amendment that allowed a majority government to appoint judges. As journalist Gideon Rachman points out, the “court was gradually packed with judges sympathetic to Orban and stripped of some of its review powers.” (95) Poland’s Law and Justice Party (2015-2023) violated the constitution by taking control of the public broadcaster and firing experienced presenters and journalists in favour of party sympathizers. (Applebaum, 5). They also purged the civil service. In all cases, these steps served to undermine checks on party power.

Conclusion

As historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat points out, “authoritarianism remains a surprisingly fuzzy concept.” Scholars have defined it in contrast to liberal democracies and totalitarianism and have identified old and new authoritarian versions, the latter being a less overtly oppressive system that retains elements of liberal democracies such as elections – fair or otherwise.

Another approach to understanding authoritarianism is to step away from a focus on definition and examine authoritarian methods. Paul Brooker describes this approach as “less interested in the tradition ‘who rules’ than in the wider question of ‘how do they rule?’ and particularly their methods of control.” (14) This approach has been taken up by scholars such as Ruth Ben-Ghiat who prefer to focus on authoritarian practices, or what some refer to as the “authoritarian playbook.” Such an approach allows us to identify, for instance, how regimes as diverse as Mussolini’s Italy and Orban’s Hungary identified enemies of the state to foster division, erode checks on executive power and prolong stays in power. In this spirit, we devote the subsequent blogs in this series to these authoritarian practices.

Our next blog in this series – The Authoritarian Playbook: An Overview

Sources

Applebaum, Annie. Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism. Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 2020.

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Cleveland: Meridin Books, 1958

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. Strongmen: From Mussolini to the Present. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2020.

Bongiovanni, Bruno, and John Rugman. “Totalitarianism: The Word and the Thing.” Journal of Modern European History / Zeitschrift Für Moderne Europäische Geschichte / Revue d’histoire Européenne Contemporaine 3, no. 1 (2005): 5–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26265805.

Brooker, Paul. Non-Democratic Regimes: Theory, Government and Politics. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Cave, Peter. The Big Think Book: Discover Philosophy Through 99 Perplexing Puzzles. London: One World Publications, 2015.

Davis, Kenneth. Strongman: The Rise and Fall of Democracy. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2020

Dikotter Frank. How to be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Franz, Erica, Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Friedrich, Carl and Zbigniew K. Brzezinski. Totalitarianism Dictatorship and Autocracy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965.

Glasius, Marlies. What authoritarianism is and is not: A practice perspective. International Affairs. 94. 515-533. 10.1093/ia/iiy060. 2018

Law, Diane. The Secret History of the Great Dictators. London: Magpie Books, 2006.

Kohn, Jerome. “Arendt’s Concept and Description of Totalitarianism.” Social Research 69, no. 2 (2002): 621–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971564.

Levitsky, Steve and Lucan Way. Revolution and Dictatorship: The Violent Origins of Durable Authoritarianism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2022.

Linz, Juan. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder, CO and London: Lynne Rienner. 2000

Nisbet, Robert. Review of Arendt on Totalitarianism, by Hannah Arendt. The National Interest, no. 27 (1992): 85–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42896812.

Przeworski, Adam. “A Conceptual History of Political Regimes: Democracy, Dictatorship, and Authoritarianism.” New Authoritarianism: Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century, edited by Jerzy J. Wiatr, 1st ed., Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2019, pp. 17–36. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvdf08xx.5. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

Scruton, Robert. Dictionary of Political Thought. London: The MacMillan Press, 1982.

Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2018.

Wiatr, Jerzy J. “Autocratic Leaders in Modern Times.” Political Leadership Between Democracy and Authoritarianism: Comparative and Historical Perspectives, 1st ed., Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2022, pp. 74–116. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv27tctmb.8. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

You must be logged in to post a comment.