For we hold that a man is justified by faith alone, apart from the works of man. Martin Luther

Historians are clear about the far-reaching impact of what came to be known as the Protestant Revolution that began in the 16th century CE. J.M. Roberts describes it as “the great crisis which shook western Christianity and destroyed the old medieval unity of the faith in the early sixteenth century forever.” (538). At one point, the Catholic Church, headed by the Holy Roman Empire, offered a unified vision of the world and the afterlife. This consensus changed with the Protestant Reformation lead by the determined and articulate Martin Luther (1483-1546).

The Holy Roman Empire and Catholic Reform. The Holy Roman Empire arose from a desire to create a Christian version of the Roman Empire in the West and a counterweight to the Byzantine Empire in the East. Ultimate authority resided with the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, who often vied for supreme power. Together they faced many threats to Catholic unity – the rise of nation-states, nationalism from Germany and other states, religious wars, debt, and an increasingly evident corruption among clerical ranks- that encouraged dissent and calls for reform.

Calls for reform did not begin with Martin Luther. As J.M. Roberts writes, “The fifteenth century had been marked by a deep, uneasy devotional swell: there had been a sense of looking for new answers to spiritual questions, and of looking for the outside the limits laid down by ecclesiastical authority. (536) Peasant revolts against clerical authority erupted in various parts of Europe. Jan Hus (1372-1415) and other religious reformers spoke against church corruption and control over spiritual practices. Devout Catholic and Christian humanist Desiderius Erasmus criticized clerical corruption and called for more inward Catholic worship and abandoning Catholic traditions such as confessions and sacraments. He also criticized clerical corruption.

Rome, of course, did not welcome criticism and censored public opinion – a task increasingly difficult with the advent of the printing press in c 1440. In 1501, Rome issued a papal bull ordering the burning of all books questioning church authority. Rome also forbid the printing of books without church approval. Criticism of the papacy could lead to Imprisonment and execution. After being excommunicated and receiving a Papal Bull, Rome executed an unrepentant Jan Huss for refusing to recant his calls for reform. Speaking out against the Roman Catholic Church required courage and conviction. Martin Luther, a relatively unknown scholar in Wittenberg, Germany, had an abundance of both qualities.

Martin Luther (1483-1546). Martin Luther became a monk in 1505, then professor of Theology at Wittenberg, Germany. Rigorous biblical studies lead him to interpretations that differed from accepted Catholic beliefs, especially around salvation. Catholic doctrine advocated that salvation could be gained through faith and good works, particularly the Catholic practice of sacraments. Luther disagreed. Salvation, he insisted, could only be granted by God. Efforts to achieve his grace through penance and good works were misguided and futile. Human actions could not persuade God.

As a devout Catholic, Luther did not want to split the Church. His conviction challenged the penitential system fundamental to Catholic belief and practice and undermined Rome’s long-reaching authority. As it stood, he kept his challenge relatively private. It would take, writes Thomas Cahill, “the prompting of an unusually shameless and aggressive display of ecclesiastical corruption to prompt Luther into the public challenge. (147).

Rome offered such a display.

A Prompting. In 1515, Pope Leo X authorized the sale of indulgences, paper certificates granting salvation. Roman officials travelled Europe collecting funds from those wanting to avoid purgatory. They found many buyers, and indulgences became a significant source of revenue for a papacy under financial strain from ongoing wars, patronage, and building projects, most notably St. Peter’s Basilica.

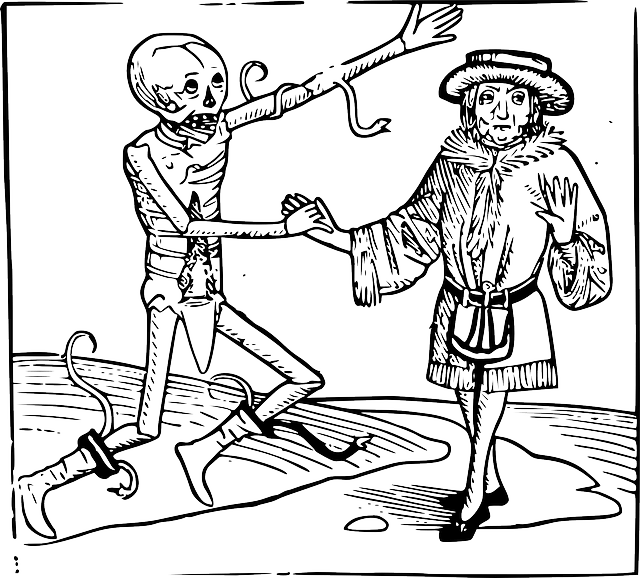

For Luther, the sale of indulgences itself was misguided. How officials, in particular Johann Tetzel, sold them intensified his ire. Tetzel, a German Dominican monk, sold Indulgences in Germany with zeal and style, using the slogan “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.” William Manchester describes the monk as “a sort of medieval P.T Barnum.” (134). Disgusted, Luther set about writing a series of theses criticizing the sale of indulgences and set in motion a series of events that would Christendom in Europe.

95 Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences In 1517, some historians alleged, Luther posted his 95 Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences on the church wall in Wittenberg. Others like Thomas Cahill maintain that Luther sent his theses, accompanied by a very respectable letter to Archbishop Albrecht, who passed it along to Rome. (p?) Either way, Luther directly challenged Catholic doctrine and the Pope himself. Luther did take direct aim at Pope Leo X, saying if the Pope could grant salvation, he could offer it for free or even give indulgence revenues to the poor. It was a direct challenge to papal authority and a condemnation of a vital income stream for a debt-ridden Rome.

Spreading The Word. Luther’s protests spread quickly. Printers (without Luther’s permission) circulated thousands of copies of his theses, including many in German. Most people could not read, but those who could verbally spread his critique of indulgences, striking a nerve with people already resentful of Rome’s extensive authority and blatant corruption. Some saw opportunities. For German princes, a reduced papal presence in German lands meant more independence and even access to Church lands.

Luther followed up his theses with three pamphlets that further criticized the system of sacraments. He also argued that priests should marry and encouraged translating the Bible into languages like German to allow people a more direct relationship with sole authority. Luther was on a roll.

Rome Responds. His protests reached Rome, who demanded he recants his statements. When Luther refused, they charged Luther with heresy. Pope Leo X considered summoning Luther to Rome, but Frederick the III intervened. Knowing Luther might not return from Rome, Frederick convinced the Pope to have Luther state his case in front of the Diet of Worms (a deliberative assembly of the Holy Roman Empire), presided over by the Holy Roman Emperor himself Charles V.

Why did Frederick III protect Luther? How could he persuade Leo X to allow Luther to present his case in Worms? Some historians have pointed to the growing anti-papal sentiment among Germans who sought more self-determination and less Roman taxes and political meddling. Handing over Luther to Rome would be a sign of weakness and compliance. Moreover, Frederick himself found Tetzel’s actions offensive and yet another example of Rome extracting money from his territory. Ruling an increasingly nationalist and ani-Papal Saxony and holding an upcoming vote for the Holy Roman Emperor gave Frederick some clout. Leo X conceded.

Luther Answers to Rome. In 1521 Martin Luther presented his case in front of the Diet of Worms. Luther stood his ground, identifying the Bible as the only authority and defying officials to demonstrate contradictions between his theses and the Holy book. A frustrated Charles V proclaimed him a heretic and forbade citizens to promote Luther’s ideas. Knowing Luther was in danger, Frederick III lobbied for Luther’s safe passage to Wittenberg hid him in Germany.

Conclusion Luther avoided execution, and Rome could not stem the tide of protestant revolt. Farmers, in particular, acted out violently. Luther condemned these protests as going beyond the laity’s boundaries of obedience. The demise of Christian unity also opened the way for new sects such as Calvinism, Anglicanism, and Anabaptism. Rome actively implemented many reforms – collectively known as the Catholic Reformation- but would not regain Christian unity in Europe. A series of religious wars during the last half of the 16th century hardened divisions throughout Christendom. Eventually, religious pluralism became the norm in most countries.

The Protestant Reformation is a convenient term for religious upheavals that were neither coordinated nor mutually supportive. Moreover, it is difficult to pinpoint its origins. As religious scholar Karen Armstrong points out, “we don’t know exactly why ‘the Reformation’ happened. Many factors mingled together- nationalism in cities (especially Germany), the printing press, clerical corruption, a greater sense of individualism, and of course, Luther himself – to foment a movement that brought fundamental changes to Europe and the World.

Selected Bibliography

Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. New York: Ballantine Books, 1993.

Boorstin, Daniel J. The Seekers: The Story of Man’s Continuing Quest to Understand His World. New York: Vintage Books, 1999.

Cahill, Thomas. Heretics and Heroes: How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Created Our World. New York: Anchor Books, 2013

Cooke, Tim. ed. National Geographic Concise History of World Religions. Washington D.C. National Geographic, 2011.

Gonzalez, Justo L. The Story of Christianity. Volume 2. New York: HarperCollins, 2017

Manchester, William. A World Only Lit By Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1992.

Roberts, J.M. The Penguin History of the World. London: Penguin Books, 1988

Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization. Volume B: 1300-1815. Boston: Wadsworth, 2012.

Stearns, Peter L. World Civilization: The Global Experience. New York: Addison-Wesley Education Publishers, 2001.